|

The Life of the Maharanis, continued..... Padmini The story of Padmini, a princess of Chittorgah, is perhaps even sadder. Though she was married already, her beauty became known to the king of Delhi and he determined to see her for himself. Given the seclusion women lived under, this was highly irregular, but in order to prevent war Padmini agreed that he might see her, but only in a mirror. The mirror was set in a high tower, overlooking the small lake palace where Padmini spent her summers. When the King was installed in front of the mirror, Padmini came to the window in the lake palace and lifted her veil. We stood in this very room, and reached the conclusion that the King must have had excellent eyesight, for the window was so distant, her face must have been a mere dot on the mirror. However, he fell madly in love with her, and determined to carry her off. He lay siege to the fort and defeat became inevitable. At this time Padmini and all the women of the fort committed Jauhar, a type of ritual suicide in which all the women go to their deaths on a funeral pyre while the men open the gates with the aim of dying in battle. Only so could the honor of the Rajput be preserved. Jauhar was committed three times in the history of Chittorgah, before the fort was abandoned. Perhaps that is why it has such a desolate, dusty appearance today. |

|

The Kama Sutra tells us a good deal about the education of the high born young woman as she prepares for marriage. In fact, apart from a grounding in the theory of the erotic arts, it mentions 64 specific arts and sciences which are 'essential'. They seem to include just about every art and craft practiced in India. Apart from music, dancing, painting and literature there is: colouring the body, hair, nails, teeth and clothes; sleight of hand and other magic tricks; ore refining and alloying; teaching birds to speak; inventing a private language; childcare; theory of war, weapons, armies, tactics and statecraft and many others. The passage concludes that knowledge of these arts will enable a woman to win fame as a courtesan. The life of a courtesan was quite different in from that of a wife. The best were highly educated, intelligent women as can be seen above and they lived relatively independent though precarious lives and were able to move freely in society. They were welcomed at social gatherings for their conversation and artistic skills, rather like the geisha in Japan or the prostitutes of ancient Greek and Roman society. They were also considered quite important in the cultural and sexual education of young, as yet unmarried men. The home of one courtesan who had the favour of a king occupies quite a prominent place in Jaisalmer, right next to the lake. The home of this lady caused quite a scandal apparently, and although I am a little hazy as to the details it had to do with her home apparently receiving prominence over a religious site. The king solved the problem by building a small temple on the roof of her flat, showing that she was lower than the gods. Despite their relative freedom and independence, courtesans of the time bore the stigma of religious impurity. A photograph of the courtesan's home can be seen here. The end of the zenana and the end of sati (hopefully) Early in the 20th century Jai Man Singh II of Jaipur married Gayatri Devi as his third wife, his stated aim to blow a little fresh air into the stifling atmosphere of the zenana. Having been brought up in a rather liberal atmosphere Gayatri Devi had to readjust to the strange world of the zenana in which she now lived, despite enjoying a rather greater amount of freedom and education than many of the women there. Her memoirs, 'A Princess Remembers', provide a record of the curious behaviours and bizarre passions of this forgotten world. She was particularly struck by the fact that many of the zenana women had would be utterly unable to cope with the outside world. Later, Gayatri Devi founded a school for girls of the aristocratic classes, with the aim of preparing them to live outside purdah. Later still, she became successful as a politician. As a matter of fact, the surest guarantees of the death of the zenana are probably economic considerations. The Rajput have fallen on relatively hard times, and can hardly afford to support such a large court, though the money they gain from tourism probably allows them to live better than many an Indian. The last recorded sati was committed by Roop Kanwar in 1996. Sati had once been reserved for the wealthiest and most aristocratic of women. It is easy to see how, in the past, when the practice was condoned, it could have spread to the wealthy 'bourgeoisie' of Rajasthan and hence down the social ladder. Such a family was Roop Kanwar's, and, let's face it, they were probably not terribly modern. India and the world were shocked by this resurrection of an illegal practice, and many refuse to believe that a healthy young eighteen-year old could willingly sacrifice her own life. If she was not murdered, it might shed some light on the matter to consider the future of a relatively high-born eighteen year old widow, even in modern India. It is my understanding that she was unlikely to remarry, or have children, the roles most valued by her society. Even if they were not valued especially, it seems to me a terrible thing to be struck at such a young age with enforced celibacy and infertility. Nor is it likely that she could easily 'leave home, get a job, and start a new life'. Her future would probably have consisted of being the lowest ranking female in her in-laws household, waiting on and caring for her sisters-in-law and their children. Even if she could return to her own family, her prospects were not much better. Many an eighteen year old in Europe or America has committed suicide with less cause than this. If there is any lesson to be learned from this sad tale, it is that a symptom is always likely to recur, until you remove the cause. |

|

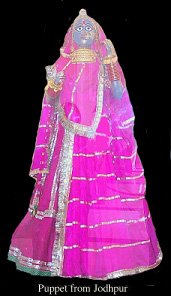

The unknown courtesan

The unknown courtesan